Marine Garden, Peacock Bridge and Wrought-Iron Fence

In 1922, one hundred years ago, James Deering (1859-1925) witnessed the culmination of years in making Vizcaya’s gardens. The grand vision for his winter haven, developed on 180 acres along the shoreline on Biscayne Bay, was the product of a collaborative partnership. Voluminous correspondence in Vizcaya’s archives sheds light onto the many experts, artists and staff that contributed to the development of the gardens between 1912 and 1922, with Deering as one of the key collaborators and designers of the landscape.

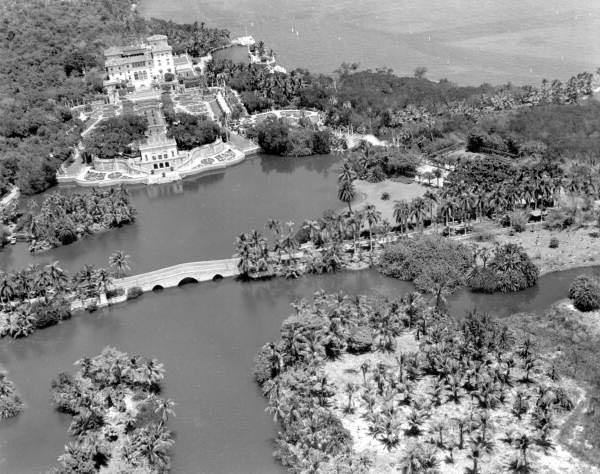

The Italian-inspired gardens adjacent to the main house and designed by the young Colombian-born landscape architect Diego Suarez (1888-1974) were well underway by 1920, and focus was placed on the Marine Garden and southern property, which was to contain a set of tennis courts, a boathouse, a staff beach, and other architectural fantasies. Located by the southeast end of the formal gardens, at the limits of the Fountain or Rose Garden, the Marine Garden would serve as an entryway into the lush tropical landscape of the former Lagoon Garden, a watery fantasia meant to capture the spirit of the Everglades. The water canal running below it created a natural division between the manicured landscaping of the Italianate gardens and the naturalistic vegetation of South Florida beyond the limits of the Marine Garden.

ON CERTAIN OCCASIONS I HAVE MADE USE OF ANIMALS, SEA GULLS, SEA LIONS, DOLPHINS, PENGUINS, TO TRANSLATE SPIRITUAL FORCES.

– Gaston Lachaise, A Comment on My Sculpture (1928)

Peacock Bridge

The Marine Garden was created as two symmetrical basins decorated with marine seashells and iron railings that connect by an arched or O-shaped bridge, called the Peacock Bridge after the eight peacock sculptures atop spiral decorative columns that graced the bridge. By the time designs for the Marine Garden were developed, Vizcaya’s artistic director and self-proclaimed architect, Paul Chalfin (1874-1959), had embraced the patronage of contemporary artists with site-specific commissions for the estate, which included the painter Robert Winthrop Chanler (1872–1930), author of a decorative screen and the ceiling painting for the swimming pool grotto, and sculptor A. Stirling Calder (1870-1945), who made the statuary decorations for the barge. For this new artistic undertaking, Chalfin engaged yet another remarkable talent, the French-born sculptor Gaston Lachaise (1882-1935), whose peacock designs would endow the Marine Garden with exotic elegance and beauty.

Born in Paris, Lachaise received academic training from the Académie Nationale des Beaux-Arts and saved money by working in the studio René Lalique (1860-1945), before moving to America in 1906 to follow his muse and future wife, Isabel Dutaud Nagle (1872 – 1957). First in Boston and later in New York, Lachaise found work with sculptors Henry Hudson Kitson (1865-1947) and Paul Manship (1885-1966), the celebrated author of Rockefeller Center’s Prometheus. His break came at the invitation to form part of the first large exhibition dedicated to modern art in America, known as the Armory Show, in 1913, and by the end of the decade, Lachaise was exhibiting in galleries, attracting new collectors, and gaining critical acclaim as a major figure in modern sculpture. The Museum of Modern Art, in New York, attested to his contributions to art by dedicating the artist, nine months before his death, the first one-person retrospective of a living sculptor in 1935.

In the exhibition catalog, the art critic and curator of the show, Lincoln Kirstein (1907-1996), wrote that Lachaise was offered Vizcaya’s commission after Manship had declined. Nevertheless, Lachaise was at the forefront of the modernist movement and producing private commissions and public works; and his artistic circles included multiple figures with connections to Chalfin. These not only included his friend Paul Manship, who hosted Lachaise’s wedding supper in 1917, but also Robert Winthrop Chanler and the socialite artist, patron and collector Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney (1875-1942), who not only participated in exhibitions with Lachaise but shared proximity to his studio. Thus, while it remains unclear how Lachaise gained the commission, it is unquestionable that the results would have been incredibly different had it not been for him.

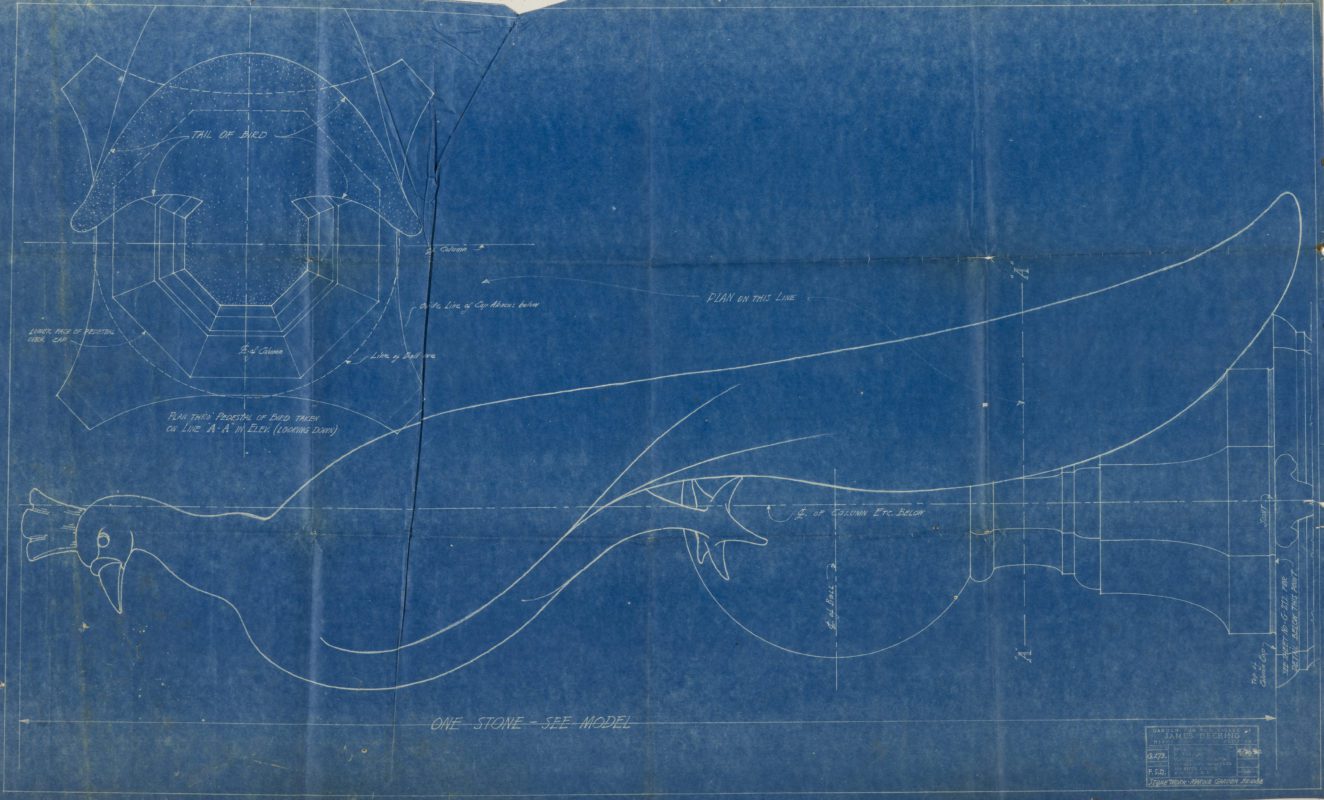

For Vizcaya, Lachaise was to create a set of two life-size peacocks with their heads facing each other. These would be raised on spiral columns with carved vines and grapes after Chalfin’s design, possibly inspired by a set of gilded columns owned by Charles Deering (1852-1927) in his Cutler Bay residence. Once Chalfin approached Lachaise with the proposal, the artist submitted an estimate for the work costing $1,000 per model, of which there would be two, and an additional $400 for a two-week period of onsite work to “put the finishing touches.” Chalfin agreed to pay the artist in three installments: one-third up front, one-third when half completed, and the balance when approved and the work entirely completed. A letter from Deering with Chafin’s thoughts on the design followed: “Ask him [Lachaise] to make them recognizably distinct in gesture one from the other, and say to him that the delicacy of the problem to me seems to be to keep them at the same time simple as we are agreed they should be, but not at all oriental-merely stoney-and practical for a soft stone at that. If they would look Roman-ancient Roman-so much the better -if not, they can look like a negligent bit of Italian garden detail-but not oriental.

With instructions in hand and an architectural drawing sent from Chalfin’s office, Lachaise proceeded to create “two peacocks with ball and finial” in plasticine for his patron’s approval. On December of 1920, Chalfin approved the models, which were consequently sent to the Menconi Brothers, who would pack and ship them to Miami. Once on-site, local workers were entrusted with the carving of both the columns and the peacocks on the native stone after Lachaise’s plaster models, but it remains unclear if Lachaise traveled to work on the finishing touches himself. The full layout of the Peacock Bridge, featuring eight columns, each topped by a short-tailed peacock, was fully realized in 1922, coinciding with the completion of the gardens.

Following Deering’s death in 1925, Vizcaya was inherited by the family, ultimately passing down to his nieces, Marion Deering McCormick and Barbara Deering Danielson, who were titled as Deering’s favorites by journalist Henry Wales. In 1942, the southern property was sold to the Catholic Archdioceses, and the property line was cut through the Peacock Bridge, breaking the symmetrical design in two. With the perils of time, the stonework of the Marine Garden deteriorated, including the peacock sculptures that saw several hurricanes and multiple restoration efforts before they were finally taken down as part of a conservation project in 2004.

Although iron is the least expensive of all metals, there is no other material that lends itself to more beautiful treatment.

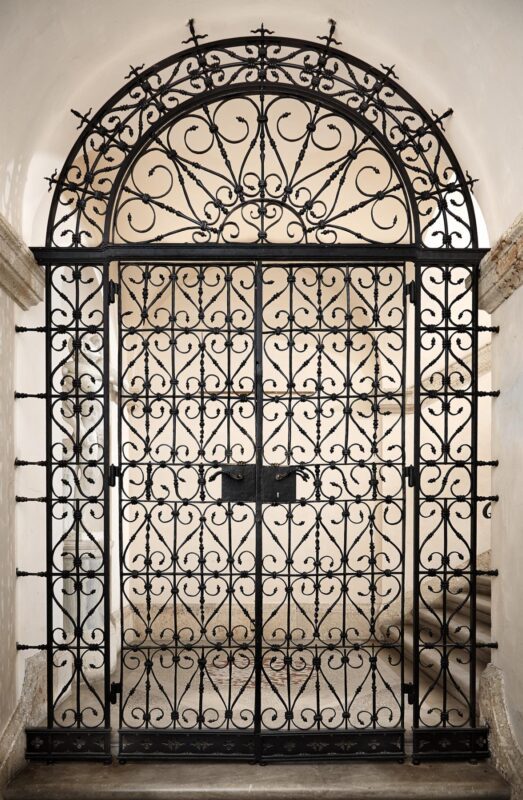

Wrought-Iron Fence

The Marine Garden was separated from the Rose Garden by an ornate wrought iron fence with two gates, measuring a total of approximately 31 feet long and 6 1/2 feet tall. Like many other gates and grilles featured in the gardens, the design originated from European grilles dating from the sixteenth to the eighteenth centuries that Deering bought from art dealers in years prior. These antique objects were either used as a whole or altered to suit the needs of the landscape design, and at times they were combined to reflect Chalfin’s desired aesthetics.

For the Marine Garden gate, Chalfin and his office in New York City produced architectural drawings using as a source of inspiration a pair of seventeenth-century Italian grilles acquired from Lavezzo & Co. Although now lost, the acquisition was recorded in Vizcaya’s objects collection card catalog as “architectural part 156” (A.P. 156) with a handwritten inscription noting the pair. The European pieces formed two fixed sections glancing a center panel of a new fabricated item with operable outer sections of the same design. The skillful hand behind the production of this elaborate ironwork was the master blacksmith Samuel Yellin (1884-1840), one of the most important metalworkers of his era and a major figure of the American Arts and Crafts movement, both as a designer and metalworker.

By 1920, Yellin was familiar with the magnificent estate Deering was building in South Florida. He had already crafted beautiful ornamental and functional items for the Main House, as the iconic bell pulls, the elevator doors and the organ screen grille. His work in the gardens was also extensive and included repairing existing antique iron works of European origin, combining them, as well as creating new contemporary pieces. Yellin was keenly interested in referencing historical material in new and innovative ways that aligned with Vizcaya’s European-inspired aesthetics. Moreover, his sensibility for design and technical skills made him a perfect candidate for the job at Vizcaya.

Most if not all garden-related commissions were bids worked through the contractor, Fred T. Ley. As early as February of 1920, Chalfin’s office was requesting estimates for a new gate, and five months later, Ley informed Yelling that he was to make “all additional new iron work for Rose Garden on all gates drawing A.P.156, Gate, Grille Cresting & Braces, as shown on Blueprints G250 and G255, all of Swedish Iron, for the sum of $4,500.00.” Once Yellin accepted the work, the European grilles were trucked from New York City to Philadelphia, where Yellin established a successful shop in 1909 and remains in operation today.

As work progressed in the garden, changes were made to the design yet, by December of the same year, Yellin had completed “work on old gates A.P.156, also gate, grille, cresting and braces shown on architect’s blueprints G-250 and G255.” The Rose Garden gates and grilles referenced in Yellin’s letter include furnishings for both the Marine Garden Gate and the Rose Garden Hedge, consisting of three grilles at the entrance to the mangrove hammock and the staff bathing area, now lost. The final gates were sent down to Miami and installed at Vizcaya sometime between March and June of 1921, as noted in Chalfin’s progress report of June 10: “large gates between Rose Garden and marine Garden set. Cleaning and painting are the same. This is the last piece of ironwork.”

Yellin’s beautiful wrought iron gates for the Marine Garden would only withstand the tropical climate for a few years. Like much of the property, the gates sustained damages from the Great Miami Hurricane of 1926 following Deering’s death. A few years later, the family, under the initiative of Mrs. McCormick, one of Deering’s nieces and wife of Chauncey McCormick, who was at the time president of the Chicago Art Institute, invited Chalfin back to the property to help restore the estate to its former glory with the noble idea of opening it to the public. The artistic director and consultant undertook work in the gardens in the summer of 1934, all of which he carefully outlined in a typewritten report, including “that the iron fence to the peacock bridge will be repaired under the supervision of P.C. [Paul Chalfin].” The repaired gates remained in place until 1980 when the iron gate was replaced by a local blacksmithing company. This new gate, while inferior in quality to Yellin’s, served its purpose for decades. Now, on the 100th anniversary of the completion of the gardens, Vizcaya will honor its patrons, designers, artists, and craftsmen with multiple complex conservation projects, including making a new Marine Garden fence that replicates Yellin’s original masterwork.

Support Vizcaya’s Conservation Efforts

Help Vizcaya continue to preserve its vast collection by making an online donation.

Together, we can safeguard this rich cultural heritage for future generations to explore and appreciate.