THE MAIN HOUSE

With timeless Mediterranean-style architecture, and collections dating from the early 20th-century all the way back to Pompeii, Vizcaya’s Main House was the jewel of a fledgling Miami when it was built between 1914 and 1922.

A century later, Vizcaya is just as relevant. It’s a cultural destination tens of thousands of visitors from all over the world each year and a hub for locals who want to learn, grow and connect in a setting that is truly “Miami’s home.”

FACTS ABOUT THE MAIN HOUSE

The Builder

Industrialist James Deering (1859-1925) built Vizcaya between 1914 and 1922. Deering arrived for his first winter residency in the Main House on December 25, 1916.

The Location

The Architectural Inspiration

The Innovations

The Setting

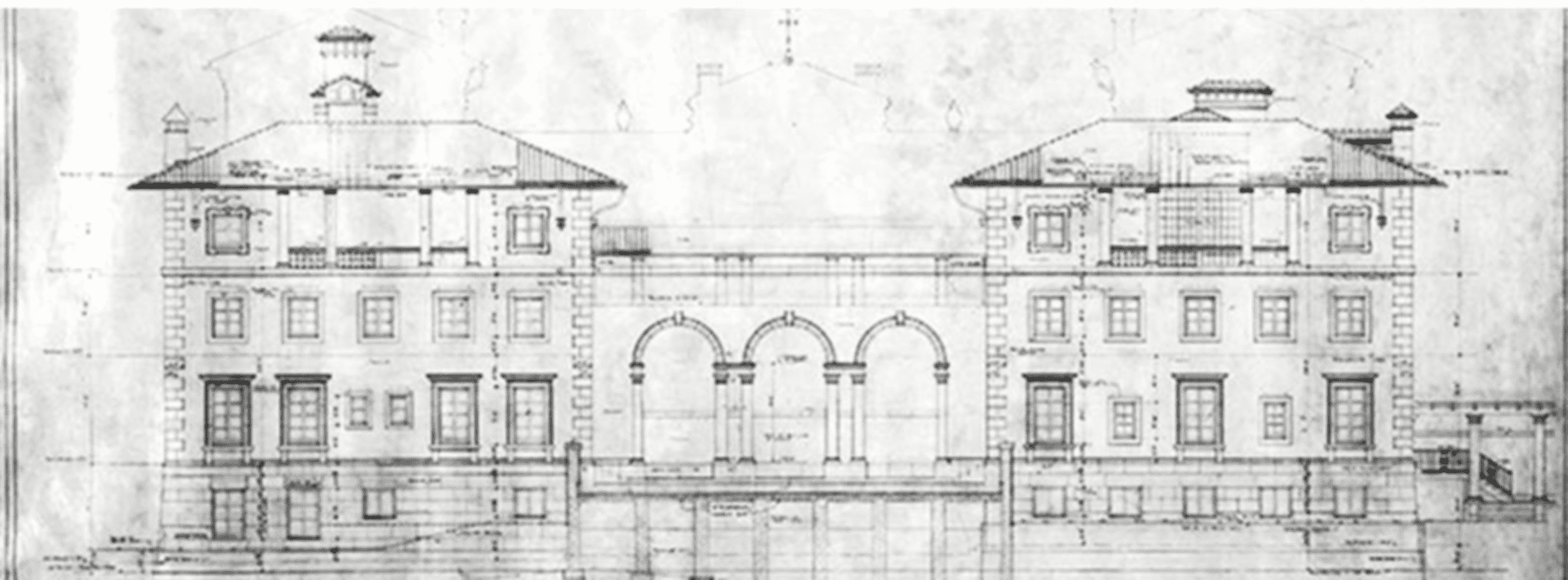

Today, Vizcaya is an oasis of silence and green, miraculously preserved just south of Miami’s modern skyline. The heart and main living area of the house is the Courtyard, which was originally open to the sky. The house was designed to take full advantage of its location on Biscayne Bay. Deering wanted Vizcaya to be approached and seen from the sea, and the east façade on the bay is the most monumental and the only symmetrical one—it opens onto a wide terrace that descends toward the water.

The other sides of the house have unique relationships with the surrounding grounds. The west façade, which has greeted visitors since Deering’s time, is simple and contrasts with Vizcaya’s elaborate interiors. The north façade accommodates one of Vizcaya’s most delightful inventions—the swimming pool that emerges from vaulted arches at the lower level of the house. The south façade opens onto the formal gardens with enclosed loggias on the first and second floors.

The Interiors

On the first floor, several reception rooms, the Library, the Music Room, and the Dining Room surround the Courtyard. The second floor housed Deering’s personal suite of rooms and guest bedrooms as well as a Breakfast Room and the Kitchen.

The interiors of the Main House were meant to suggest the passing of time and the layered accumulation of artifacts and memories. The rooms were designed around objects acquired in Italy and assembled into new compositions by Artistic Director Paul Chalfin.nnBoth the house’s aesthetic significance and modern efficiency were celebrated in architectural and engineering magazines of the time.

SUPPORT VIZCAYA’S PRESERVATION n

Help support Vizcaya’s ongoing preservation of this National Historic Landmark

ABOUT THE COLLECTION

Art Collections in the Main House

The rooms in the Main House were designed around pieces of furniture, paneling and architectural elements such as gates and fireplaces. Every object contributes to the decorative context of the room in which it resides. As such, the objects and interiors played an important role in determining the architecture of the house.

Chalfin was an expert in Italian furniture and interiors, and the rooms in the Main House reflect his interest in different periods of history. The eighteenth century was the main inspiration for Vizcaya—ranging from the asymmetrical and highly inventive Rococo to the more linear and austere Neoclassical style.

Chalfin also wanted to evoke the style of different Italian cities, and so Vizcaya has rooms inspired by Milan (Music Room), Palermo (Reception Room) and Venice (the Cathay and Espagnolette bedrooms). In Deering’s personal suite, Chalfin assembled masculine, but yet ornate, furniture of the Napoleonic era, while in the Living Room and Dining Room he followed the fashion for “modern” Renaissance interiors popular among art collectors in Europe and the United States.

Chalfin was not interested in historical consistency and he was skilled at integrating new elements of his own design into old artifacts, creating eclectic ensembles. Vizcaya was, after all, designed as a vacation house, and the décor is consistently playful and whimsical.

Nonetheless, today, Vizcaya has one of the most significant collections of Italian furniture in the United States.

Art Collections in the Gardens

The statues, busts, vases and urns that decorate Vizcaya’s gardens range from antiquity to the Renaissance and Baroque periods, and include modern art from Deering’s time.

While Chalfin’s intent was to acquire artifacts as decoration rather than to assemble a collection, the gardens do preserve a large number of important eighteenth-century sculptures representing mythological figures. These sculptures originally decorated villas around Venice, Italy.

One of the most monumental outdoor sculptures at Vizcaya is the central element of the Fountain Garden. This was designed in 1722 by Filippo Barigioni (1680–1753), the architect who created the fountain in front of the Pantheon in Rome.

What makes Vizcaya unique among American country estates of the time is the combination of these antique elements with new sculptural decorations by contemporary artists, such as Gaston Lachaise (1882–1935), Charles Cary Rumsey (1879–1922) and Robert Winthrop Chanler (1872–1930). Chanler was responsible for the ceiling of the swimming pool, an extraordinary stucco bas-relief representing the underwater flora and fauna of the Florida Keys.

The most outstanding of Vizcaya’s twentieth-century features is the Barge, sculpted by Alexander Stirling Calder (1870–1945). Located in the water in front of the Main House, the Barge is a monumental breakwater shaped as a boat and decorated with carvings representing mythical Caribbean creatures. During Deering’s time, there were also full-grown trees, a latticework pavilion and fountains on the Barge.

Preservation and Conservation

At Vizcaya we are constantly active in the preservation and conservation of this unique and fragile estate and its extremely varied collections. These collections include archival material and historic photographs, textiles, sculptures, paintings and furniture, monumental architectural elements and a living collection of historic plants, some of which date back to James Deering’s day. Though James Deering used high-quality materials and construction techniques at Vizcaya, the estate is more than a century old and for many years funding was not available for maintenance and capital projects.

The estate’s subtropical location on Biscayne Bay is deeply relevant to Vizcaya’s beauty and significance. This location, however, also exposes Vizcaya’s historic artifacts to saline and damp conditions and the periodic devastation of hurricanes, the first of which occurred in 1926, just a year after James Deering’s death.

With every preservation and conservation project, we first conduct archival and field research to understand how things were made and how they looked in Deering’s day. Vizcaya’s designers wanted Vizcaya to look old as soon as it was built, so we don’t strive to make things look pristine or new.

We also perform conditions assessment and materials analysis to document prior treatments and determine what approach might be best. And on each of these projects we collaborate with architects, conservators and scholars with the appropriate skills, training and experience.

BUILT TO LAST

Construction on the Main House at Vizcaya began in 1914, with founder James Deering taking up winter residency there for the first time on December 25, 1916.

RELATED STORIES

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Ut elit tellus, luctus nec ullamcorper mattis, pulvinar dapibus leo.

![Composting Done for You [GIVEAWAY]](https://vizcaya.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/Composting-Giveaway-900x600.png)