Atena Sherry

2023

In Miami, water is everywhere. It flows towards us from the vast Everglades, moves beneath our feet, and laps upon our shorelines at our Atlantic coast. Understanding the complex and interconnected ecology of South Florida is essential to combating the threat of sea-level rise and climate change today. We rely on our natural watershed for clean drinking water, but our ecosystem also sets an example of what a resilient system should look like. Recognizing our connection to the land and water is intrinsic to resiliency and sustainability.

“Urban Southeast Florida is not separate from the Everglades,” says Meenakshi Chabba, Ph.D., an Ecosystem and Resilience scientist at the Everglades Foundation. “Restoring the flow of water means getting back the historic water flows which would lead to healthy ecosystems and restore the freshwater and saltwater balance in our open waters.”

Following the Water

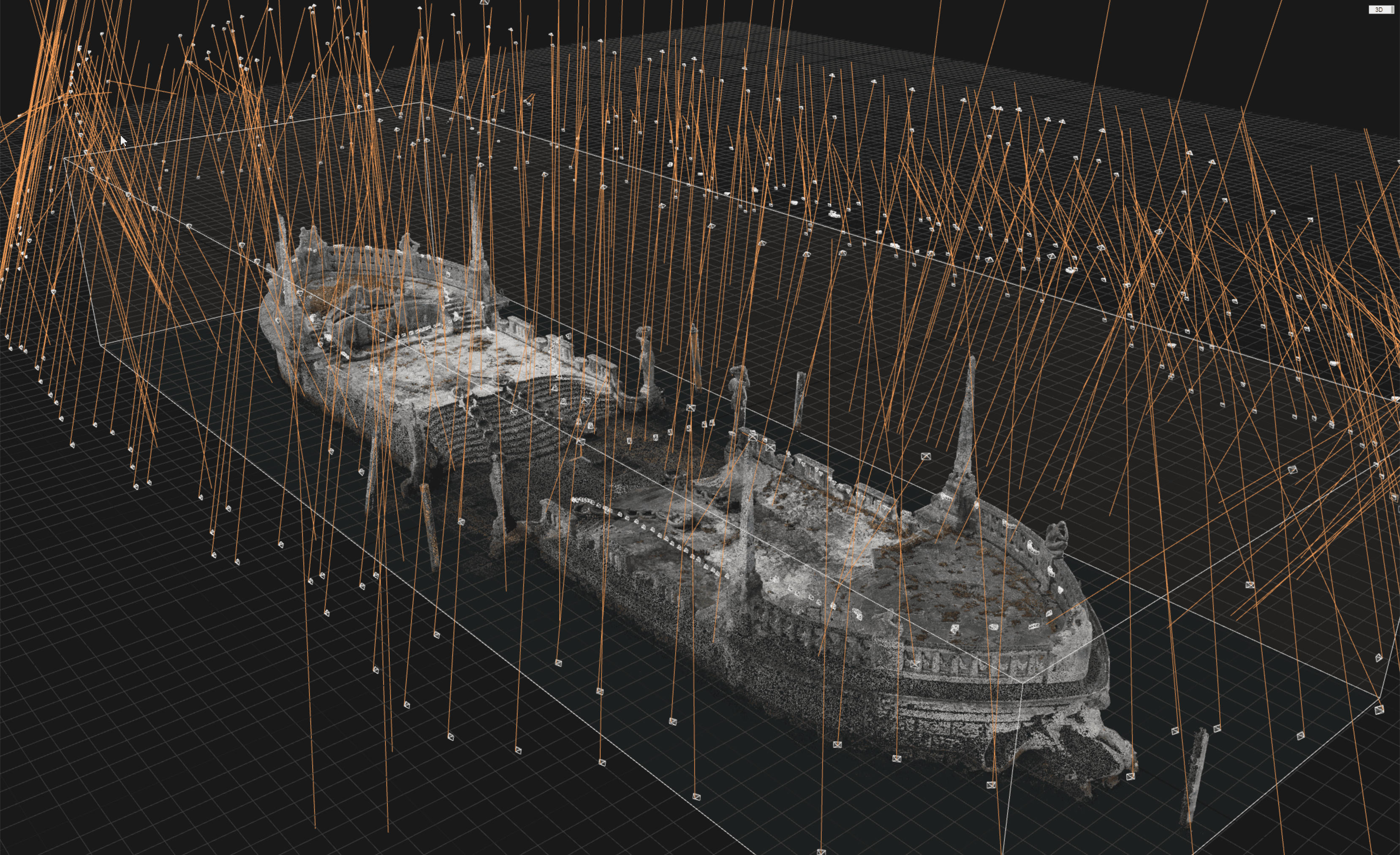

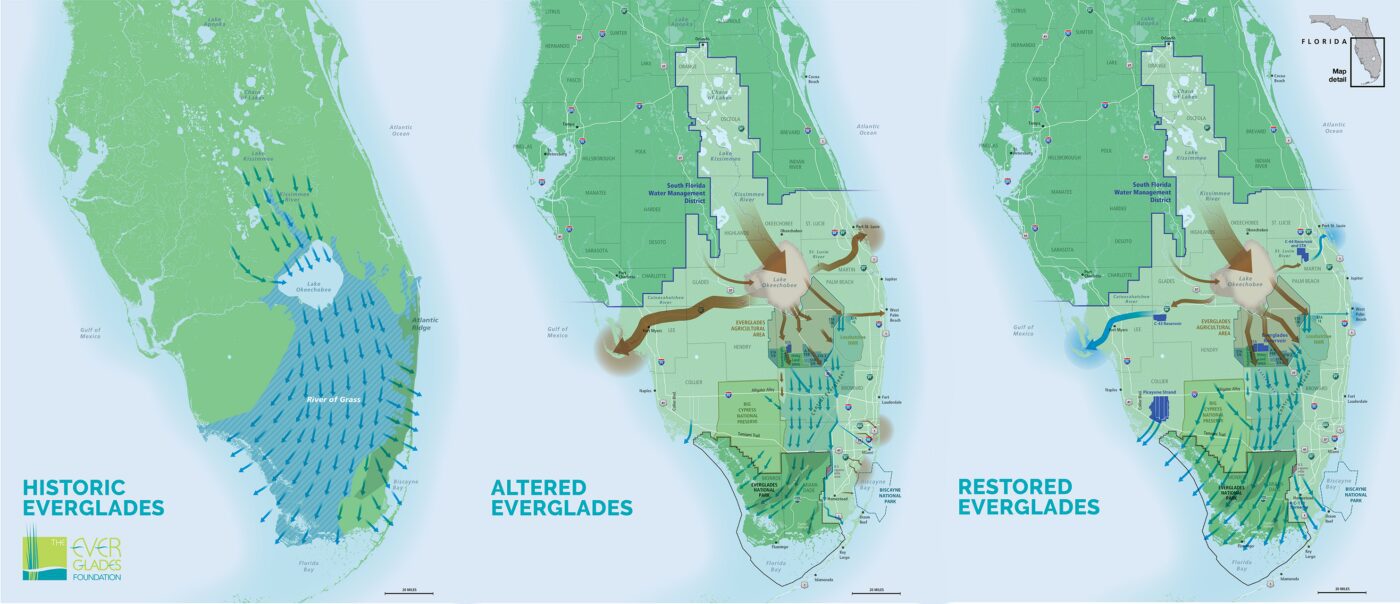

The heart of South Florida’s water flow is Lake Okeechobee where water from central Florida accumulates, eventually flowing south into the slow-moving Everglades. If the lake is a heart, the Everglades are lungs. The River of Grass’ flat topography and porous limestone formations create a shallow, slow-moving sheet flow across the landscape. Extensive marshes, sawgrass prairies, and mangrove forests help cleanse and purify the water, removing pollutants and excess nutrients.

This filtration process is vital for maintaining water quality and sustaining the delicate balance of our ecosystem. The clean sweet water naturally flows into the Biscayne Bay Aquifer, eventually mixing with the saltwater from the Atlantic that moves through the mangroves on our eastern coast.

“The flowing water in the Everglades is the primary source of aquifer recharge.” Meenakshi explained, “The Everglades is providing us a basic resiliency for people here —to keep a fundamental requirement —that’s drinking water.”

The essential functions that our ecosystem performs are naturally resilient to climate change and sea-level rise.

“If you look at the Floridian Peninsula, you can then visualize the Everglades as a natural resilient infrastructure,” Chabba explained.

The mangrove forests along our coasts, which can be observed at Vizcaya, are major stores of carbon. “They store carbon as they’re growing and sequester it,” Chabba says, “This is one of the biggest global services this ecosystem performs in keeping the planet cool.”

Combined with sawgrass, and marshes, mangroves hold together the soil at our coasts. “They stabilize the soil and build on layers of peat soil.” says Chabba. “These layers of rich organic matter not only store carbon but build elevation, which we need here in low-lying Florida, to protect against the advancing sea level resulting from climate change.”

The shoreline’s natural barrier helps mitigate storm surge flooding and protect against rising tides.

One major challenge facing our ecosystem today is saltwater intrusion. As the sea level rises, the delicate balance of sweet water and salt water is disrupted. Causing the sawgrass to die off, the peat soil to collapse, and give way to open waters.

“Those open waters are lost ecosystems,” said Chabba, “We not only are losing the soil, the carbon stored in the soils, but those healthy ecosystems are being lost.”

A History of Diversion

When James Deering built Vizcaya, the spirit of industrialization in Florida was taking hold. In the early 20th century, engineers and developers sought to convert the expansive wetlands, including the Everglades, into arable land for agriculture and urban expansion. The “drain the swamp” mentality emerged, aiming to claim the land by constructing extensive canal systems and levees to control water levels. However, the “drain the swamp” approach had significant environmental consequences, disrupting the natural water flows and intricate balance of the Everglades ecosystem.

One major disruption was the construction of the Tamiami Trail, or Highway 441, across the Everglades in 1928. At the time, it was heralded as a major industrial achievement, allowing goods and people to travel from Miami to Tampa. However, the road cuts through the River of grass, disrupting the flow of water from the northern glades to the southern marshes.

Additionally, unsustainable agricultural practices have led to the widespread pollution of Lake Okeechobee, where runoff from surrounding sugar plantations has jeopardized the health of the lake for decades.

To address these issues, the State of Florida and the Federal Government recently broke ground on the Everglades Agricultural Area Reservoir, a part of the Comprehensive Everglades Restoration Plan.

The reservoir aims to collect rainfall and water from Lake Okeechobee, clean it in treatment plants, and restore it to the natural watershed. The massive reservoir will take seven years to construct and will store about 78 billion gallons of water.

Addressing climate change calls for large-scale interventions like the EEA Reservoir and small-scale changes to developmental practices.

The Economics of Restoration

Adapting our existing infrastructure to be more sustainable will be expensive. The EEA reservoir alone is estimated to cost over 3 billion dollars. However, Chabba’s research suggests that building sustainably and restoring our ecosystem’s natural water flow will save money in the long term.

“Green infrastructure is the most cost-effective and ‘no regret’ solution to bringing about climate resiliency,” she says. Green infrastructure includes measures that use vegetation and soils to reduce the impacts of weather extremes such as flooding and extreme heat.

“You have the grey infrastructure here,” Chabba explained, “those systems are not only more expensive, but they’re maladaptive.” Grey infrastructure usually refers to the type of development techniques employed during industrialization, which historically alter the existing functions of the ecosystem.

“Everglades Restoration shows us that restoring the naturally resilient infrastructure that we have achieves much higher returns” Chabba explained, “If we didn’t have the Everglades if we let the Everglades degrade, we would have to build another super infrastructure to protect us.”

Much of Chabba’s research focuses on the economic outcomes of sustainable restoration projects. A 2016 Environmental Science and Policy study found that the monetary value of the carbon stored in the Everglades mangrove forests ranges between $2 to $3.4 billion dollars. Another study conducted by researchers at UC Santa Cruz, the Nature Conservancy, and RMS in 2017, found that mangroves averted an estimated $1.5 billion in storm damages during Hurricane Irma, a 25% savings for counties with mangroves.

Reconnecting with the Natural Landscape

It’s not always easy to feel connected to the environment when you’re sitting in traffic on I-95, or taking a bus or train through Miami. Yet, recognizing our relationship to the land and water is essential to becoming more resilient. Even in Miami’s most urbanized areas, the water from the tap comes from our aquifer. Each frontier in the fight to adapt to our changing climate or rising sea level is affected by the unique flow of water above and below ground in South Florida. Protecting the natural landscape simultaneously preserves our ability to live in this unique environment.

The next time you visit Vizcaya, take a moment to observe the natural ecosystems on the property. On Bayshore Drive, a limestone ridge hugs the Estate’s boundary leading into a preserved Rockland hammock atop porous limestone substrate. From there, the land elevation drops giving way to mangrove forests at the shoreline. The salty waters of Biscayne Bay mingle with the mangrove roots, building up the peat soil beneath. Glimpses of our natural ecosystem are all around us in Miami – if you know where to look.

Additional Content:

Explore all of Beyond Vizcaya’s content about Climate & Environment!

Atena’s Bio:

Atena Sherry is a reporter and documentary producer in Miami. She covers climate, social justice, and breaking news events across Florida. Her writing has appeared in New York Magazine, the Daily Beast, America Magazine, and more. She has produced documentaries for national television stations throughout Europe about sea-level rise and the climate crisis.