An Eye to History: Learning from Miami’s past to build a sustainable future

Atena Sherry

2023

Miami is a shape-shifting city. From 2013 to 2022, over twelve thousand new apartments were added to the city’s skyline, making it fifth in the nation for new development. Construction is booming but sea level rise and climate change are threatening all aspects of civic life. Over the next 40 years the City of Miami must spend $3.8 billion to manage stormwater and flooding alone. Historic sites, like Vizcaya, are facing unique preservation challenges as climate change looms.

To adapt, Miami must draw from its unique history, culture, and architecture to shape-shift its way to a resilient future.

Beyond Vizcaya spoke with two Miami architects, Raymond Fort, Designer, Arquitectonica, and Allan Shulman, Founding Principal, Shulman + Associates, about how Miami’s past can inform future sustainable and equitable design.

Urban Planning and Green Spaces

Flooding, failing sewage management, and heavy dependance on cars are a few of the massive infrastructure challenges Miami is facing today. Despite these, Fort thinks that Miami’s developmental history offers unique opportunities to build a sustainable city moving forward.

“At the end of the day, it’s the space in between buildings that in many ways defines the city,” he said. “We have the opportunity to build a city that has every aspect of what a modern green city should be today.”

He explained that native plants and green space play crucial roles in mitigating flooding by absorbing rainfall and helping to regulate temperatures in urban environments. Miami was built for the car as the primary mode of transportation which means it must make sweeping changes to encourage sustainable options, like walking, biking or public transit. It also has more flexibility.

“Here, we don’t have centuries of development that was focused on walkability because Miami didn’t start out as a pedestrian city,” Fort, a Miami native explained. “That said, I think anyone that visits Miami experiences the lush existing natural landscape and preserving and improving that condition is something we need to be smart about as the City continues to develop.”

Older cities, like Paris, are far more walkable than Miami, but they are growing increasingly hotter because of their lack of tree coverage.

Fort believes Miami has the advantage of preserving our green spaces and increasing our walkability with new standards and building codes, like the City of Miami’s Miami 21 plan, a 2019 zoning code that takes a holistic approach to to land use and urban planning.

“Slowly, we can build our streetscape so that every project will inherently become a green project,” he said.

According to Fort, Vizcaya plays an integral role in the future of Miami’s urban fabric. “It sits at the junction that’s right in between a high-density part of town (Brickell) and a lower-density part of town (Coconut Grove),” he said. “It’s like a connector and an outstanding public green space.”

Fort postulated that Miami can become sustainable and resilient by focusing development in densely populated downtowns while integrating affordable transit to accessible public greenspaces, and incorporating native plants into urban design.

Designing for the Natural Environment

Miami was built for the car. It was also built for the heat. There are many elements of early 20th century architecture in South Florida that set examples of how to build for our natural environment.

Shulman, who wrote Buoyant City: Historic District Resiliency & Adaptation Guidelines for Miami Beach, said he approaches resiliency in a regional way. “Being resilient in Miami means acting tropical.”

He considers designs that worked pre-air conditioning. “Raising building off the ground, protecting from the rain and sun, tempering the sun that does enter the house, accenting breezes,” he said. “These issues largely go to the question of sustainability, but they are larger, because they are about livability, and creating a resilient way of life.”

Fort echoed this sentiment. “One of our biggest challenges in designing buildings today is HV/AC systems and how we cool spaces.”

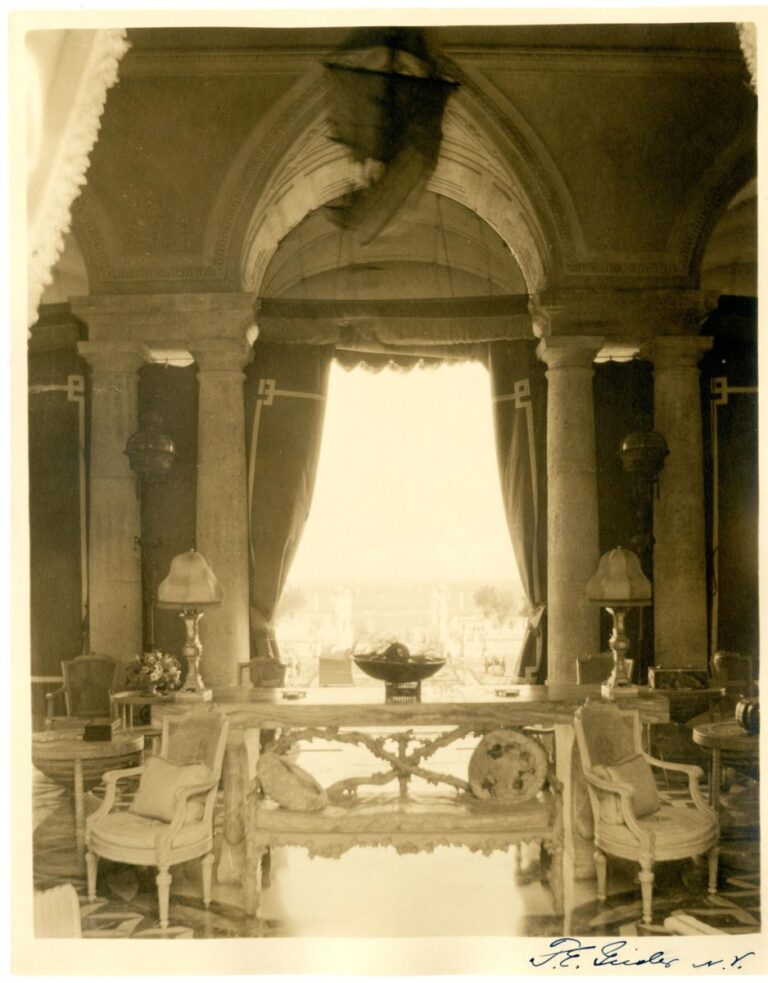

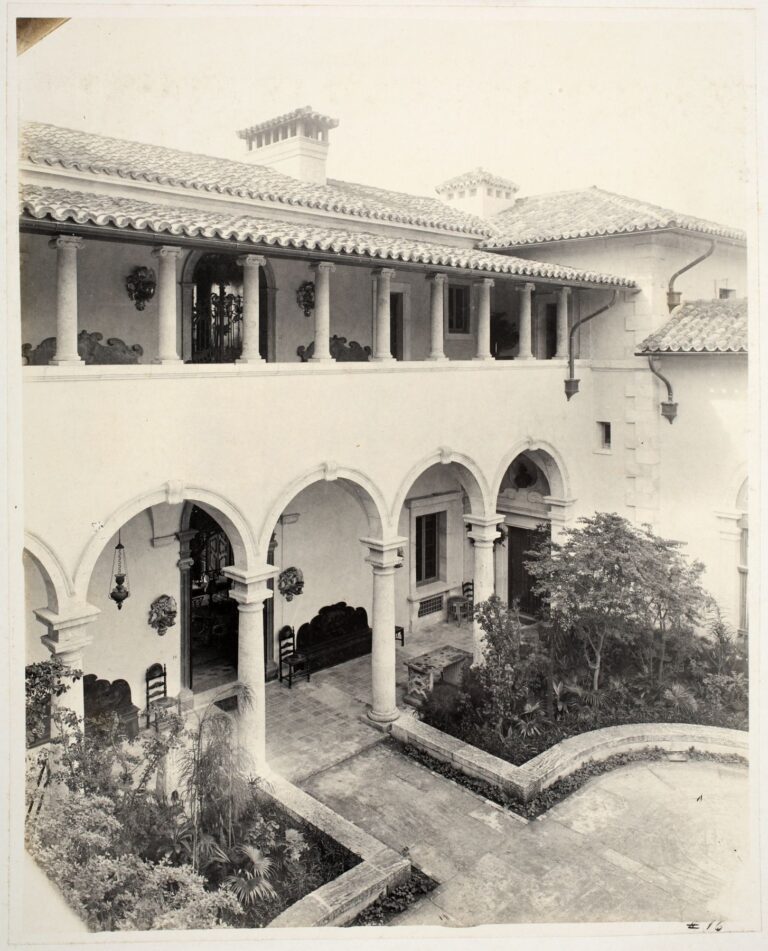

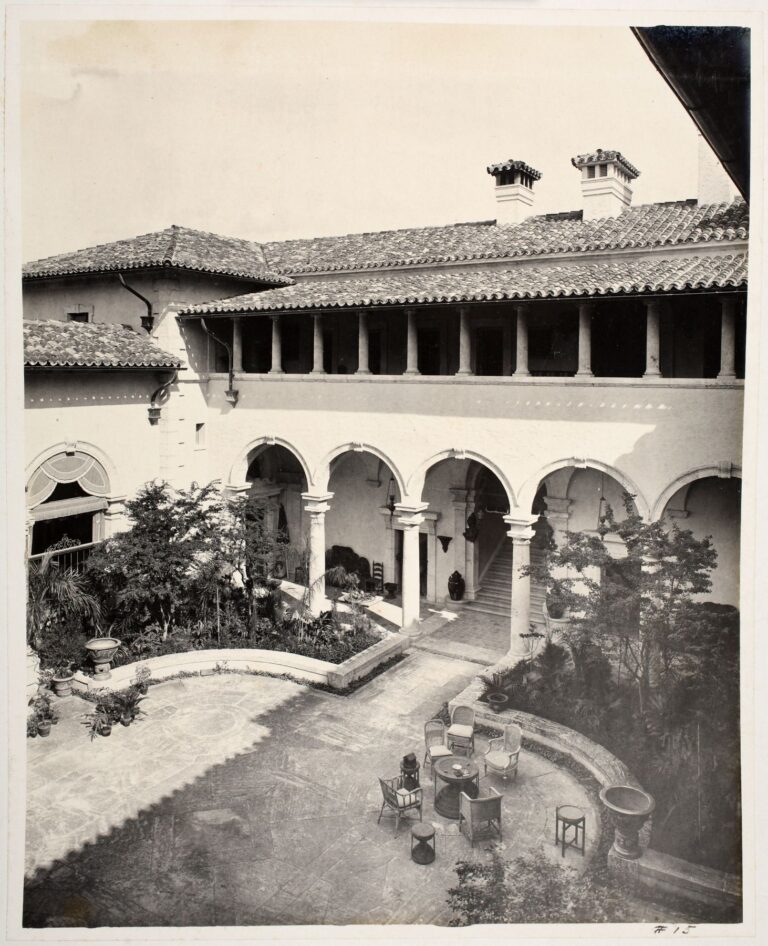

Buildings like Vizcaya, and less opulent historic architecture like the Art Deco district in Miami Beach, or shotgun homes in Coconut Grove, were all designed to stay cool in the Florida heat.

“I’m thinking of those with an inner courts or breezeways that create airflow,” said Fort. “Today, we need to consider these passive cooling opportunities.”

Other historic elements like wrap-around terraces or eyebrows over windows can be incorporated into new designs to prevent solar heat gain and direct exposure to wind and rain.

Preservation and Adaptation

Sea level rise and climate change complicate the preservation of historic buildings in South Florida.

“Older buildings are often built with lighter materials, standard glass windows and unprotected openings,” Shulman explained. “Many postwar buildings, especially homes, were built right on a slab on the ground. This makes them more accessible, but also more vulnerable, than structures that are raised.”

Shulman suggests that preservationist should think in creative ways to meet the challenge.

“In my opinion, supporting the resiliency of historic buildings might need to consider the possibility of more far-reaching changes. Buildings should be understood as organic, with the ability to grow and transform,” he said.

This approach can be inconsistent with traditional preservation and conservation thinking which usually focuses on keeping the building the same.

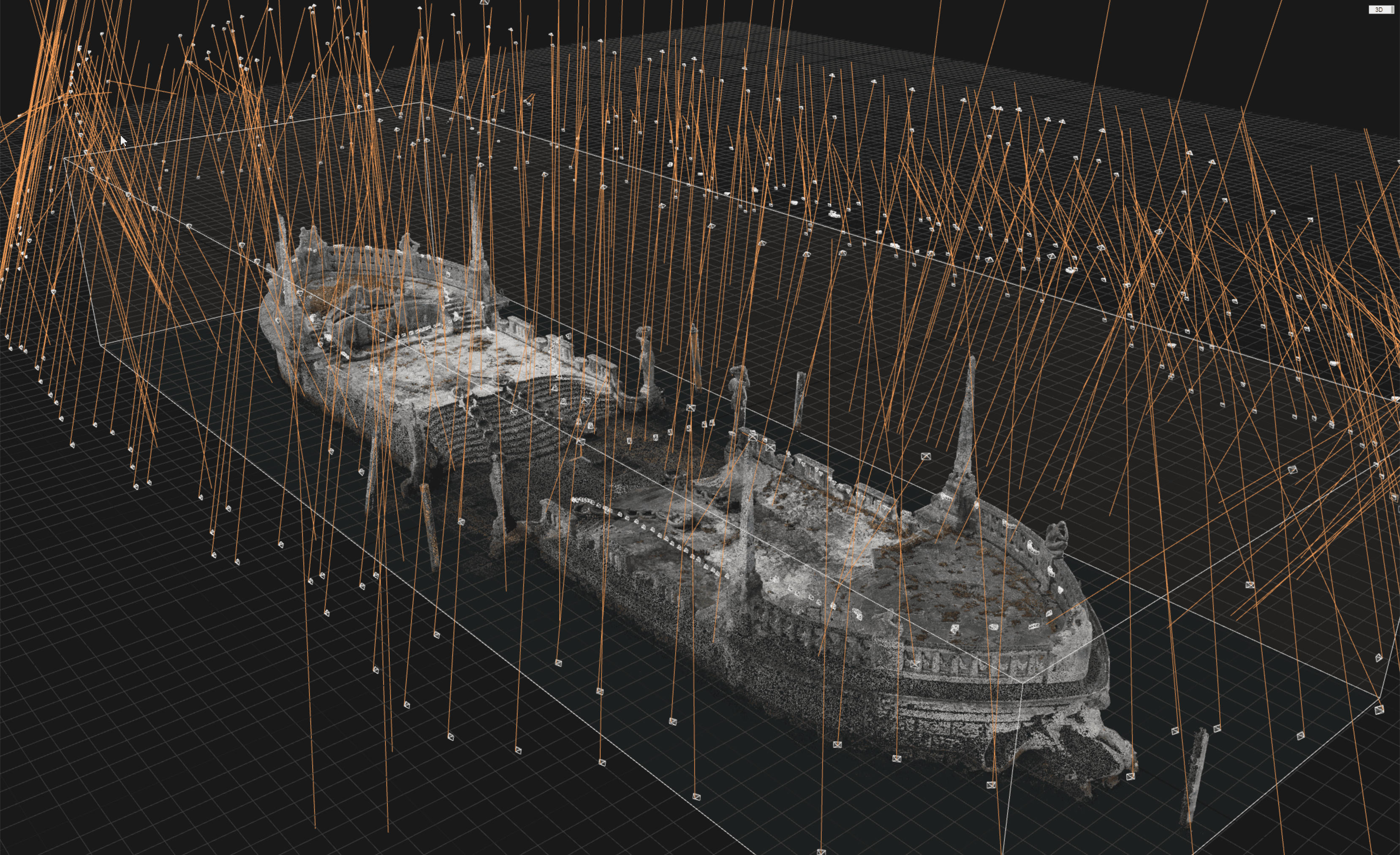

Vizcaya is using new technologies like LIDAR (Light Detection and Ranging) scanning and photogrammetry to create 3D models. These techniques allow for a better understanding of the challenges to come and create a lasting archive of how the property stands today.

Equitable Futures

Truly resilient cities are equitable cities. A sustainable future is one that serves all of Miami’s diverse socioeconomic fabric. The preservation of historic sites is integral to maintaining Miami’s cultural history, but critical thinking must be employed to ensure that the preservation serves everyone.

“If you look at the whole picture of resiliency – economic, social, functional – the heavy workload of making a historic building climate “resilient” probably makes them less resilient,” said Shulman.

“High-cost renovation work may translate to difficult business models, predicated on the highest rents and with less emphasis on future adaptability to functional changes. This may make the structure more resilient, but it becomes a less resilient component of the city.”

In his Buyont City report Shulman and his team emphasized the importance of equity in preservation, recommending the city should “engage conservancy of place, cultural identity and community as intrinsic values of preservation.”

Thinking Big and Embracing Uncertainty

Both Fort and Shulman agree that Miami must embrace it’s unique cultural and developmental history to adapt to climate change in new and unexpected ways.

“I really think that some of the landscape standards that we have in the city are unlike anywhere else. In the country or the world,” said Fort. “I think that there is a big opportunity here in Miami to create, and potentially even be this role model for an American city.”

Miami is relatively young and agile in comparison to other cities in the world, making it uniquely poised to adopt forward-thinking and bold solutions.

“We should recognize this moment offers an opening to think critically about our current practices, and to be bold in trying new approaches” Shulman postulated.

If Miami can harness a creative and intersectional approach to sustainability, one informed by it’s complicated and exuberant history, it might have a chance to address the existential threat of climate change and sea level rise.

Perhaps, as Shulman recommends, the city would do well to “embrace the experimental nature of the current predicament.”

Atena’s Bio:

Atena Sherry is a reporter and documentary producer in Miami. She covers climate, social justice, and breaking news events across Florida. Her writing has appeared in New York Magazine, the Daily Beast, America Magazine, and more. She has produced documentaries for national television stations throughout Europe about sea-level rise and the climate crisis.